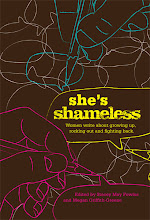

The image of a man is painted on the trunk of a tree. Its limbs rise above the man’s head and hold a small house perched atop its branches. The tree stands inside the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). Behind the tree, tiny 3D shacks are painted on clouds of orange smoke that extend up onto the wall.

The image of a man is painted on the trunk of a tree. Its limbs rise above the man’s head and hold a small house perched atop its branches. The tree stands inside the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). Behind the tree, tiny 3D shacks are painted on clouds of orange smoke that extend up onto the wall.Better known as the “Hug me tree,” it became a landmark on Queen Street West, and was transplanted to the Institute of Contemporary Culture as part of Housepaint, Phase 2: Shelter, the first exhibit to fuse street art and commentary on homelessness in the ROM.

Housepaint, which ran from December 2008 until July 5, brought together 12 of Canada’s internationally recognized street artists to paint in memory of Tent City and all those who have died on the streets.

The “Hug me tree” stood on Queen Street West until it was knocked down by a car. Neighbourhood residents rescued the tree from being tossed into the trash.

The “Hug me tree” stood on Queen Street West until it was knocked down by a car. Neighbourhood residents rescued the tree from being tossed into the trash. Toronto artist Elicser Elliot was able to infuse a new reincarnation of the tree with the same values as the exhibit. “I thought the tree brings the community together. Everybody gets around it and love is passed through the tree somehow. I was like it’s a community and from a community comes home,” said Elicser.

Tent City became home for an entire homeless population that began growing on an empty lot at the base of Parliament Street as early as 1996. For many, the shantytown represented an act of solidarity and civil disobedience, as residents utilized society’s garbage to construct an independent way of life—until they were evicted in September 2002.

Tent City became home for an entire homeless population that began growing on an empty lot at the base of Parliament Street as early as 1996. For many, the shantytown represented an act of solidarity and civil disobedience, as residents utilized society’s garbage to construct an independent way of life—until they were evicted in September 2002.Housepaint’s curator, Devon Ostrom, and co-founder of them.ca, was commissioned by Luminato Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity in June 2008 to do live painting on the site where Tent City once stood, in collaboration with Manifesto Community Projects.

On the packed gravel where up to 200 people lived an alternatively housed existence, he invited Canadian street artists, Case, Evoke, Lease, Dixon/Royal, Cant4, Elicser, Starship, EGR, and Other to each paint canvas houses in homage to former residents. The sizes of the structures were representational of Torontonian’s incomes, with two low, two high and six middle class houses.

On the packed gravel where up to 200 people lived an alternatively housed existence, he invited Canadian street artists, Case, Evoke, Lease, Dixon/Royal, Cant4, Elicser, Starship, EGR, and Other to each paint canvas houses in homage to former residents. The sizes of the structures were representational of Torontonian’s incomes, with two low, two high and six middle class houses.  While painting on the site, Toronto artist Erica Gosich Rose (EGR) felt an undertone of reality.“Since it was such a sensitive topic I had a hard time thinking of what to do. I wanted to react and comment in a way that wasn’t just going to make me cry while painting and totally break down. Because the whole situation and struggle that these people have faced is so immense I wanted to bring an element of hope,” she said.

While painting on the site, Toronto artist Erica Gosich Rose (EGR) felt an undertone of reality.“Since it was such a sensitive topic I had a hard time thinking of what to do. I wanted to react and comment in a way that wasn’t just going to make me cry while painting and totally break down. Because the whole situation and struggle that these people have faced is so immense I wanted to bring an element of hope,” she said.  She was inspired by Gustav Klimt’s painting “Hope II” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and wanted to capture the unity of that feminine family. A pregnant woman was sprayed on the roof of the tall house that she painted. The woman’s head was bent down, breasts bare, a golden mosaic of patterned cloth hanging down over her stomach and onto the wall. The other walls were filled with the images of three women draped over one another, eyes closed, hands raised in prayer.

She was inspired by Gustav Klimt’s painting “Hope II” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and wanted to capture the unity of that feminine family. A pregnant woman was sprayed on the roof of the tall house that she painted. The woman’s head was bent down, breasts bare, a golden mosaic of patterned cloth hanging down over her stomach and onto the wall. The other walls were filled with the images of three women draped over one another, eyes closed, hands raised in prayer.  When the ROM invited Ostrom to bring the street art into the gallery setting, he wanted the show to retain some of the fluid spontaneity that is part of graffiti culture.

When the ROM invited Ostrom to bring the street art into the gallery setting, he wanted the show to retain some of the fluid spontaneity that is part of graffiti culture. “I didn’t really want to sort of plunk down a bunch of street art in the gallery. I wanted to bring in a chance for the public to get to meet street artists and see their work evolve. I think people have gotten the opportunity to look into a world they don’t normally get that much access to,” said Ostrom, who oversaw artists adding new pieces to the exhibit roughly every month and-a-half, like an organic game of telephone messages which each interprets differently.

One of those additions was “Evoke/Contraction” by Patrick Thompson (Evoke). The large façade of a suburban house and garage were affixed to a slanted wall of the exhibit with the words “Bomb the suburbs” scrawled under the roof. Multicoloured paint splatters exploded across it, representing homelessness and the lack of housing as a national disaster.

One of those additions was “Evoke/Contraction” by Patrick Thompson (Evoke). The large façade of a suburban house and garage were affixed to a slanted wall of the exhibit with the words “Bomb the suburbs” scrawled under the roof. Multicoloured paint splatters exploded across it, representing homelessness and the lack of housing as a national disaster.

Elicser believes that graffiti is appropriate media to comment on homelessness because both cultures are often misunderstood and share the same space, which he realized while he was painting a wall one day and a woman urinated beside some nearby dumpsters.

“I was just like, ‘Why are you peeing right there?’ And it just clicked to me that that was her home and I was sort of painting in her living room. So after that I didn’t get that mad about her peeing in front of my wall, because I sort of realized that it was her wall as well,” said Elicser.

Accessibility was the biggest drawback of exhibiting in the ROM for those who couldn’t afford the $22 admission fee. Ostrom tried to address this issue by giving free tours to different youth and homeless groups, as well as advertising free visitor nights. He also wanted to address the larger themes of homelessness and street art by using Housepaint as a platform for the voices of activists, artists and city councillors.

Accessibility was the biggest drawback of exhibiting in the ROM for those who couldn’t afford the $22 admission fee. Ostrom tried to address this issue by giving free tours to different youth and homeless groups, as well as advertising free visitor nights. He also wanted to address the larger themes of homelessness and street art by using Housepaint as a platform for the voices of activists, artists and city councillors. Eric Weissman has been following the lives of Tent City residents on film since May 2002 in his documentary, Subtext: real stories, and was invited to screen his film at the ROM, which was available for visitors to view in the exhibit.

He began filming when there were only six houses on the lot, as members of the community struggled with addictions, scavenged and built shelters, cooked together and shared their lives with him on camera.“The only difference between Tent City and a small little neighbourhood is they don’t have driveways and garages. They weren’t borrowing their friend’s boat or their friend’s driver to go to the golf course but they would borrow his hammer or they would borrow cigarettes,” said Weissman.

He began filming when there were only six houses on the lot, as members of the community struggled with addictions, scavenged and built shelters, cooked together and shared their lives with him on camera.“The only difference between Tent City and a small little neighbourhood is they don’t have driveways and garages. They weren’t borrowing their friend’s boat or their friend’s driver to go to the golf course but they would borrow his hammer or they would borrow cigarettes,” said Weissman. He also witnessed residents’ forcible removal by the city and land owner, Home Depot, who claimed that fire risk and ground contamination on the former garbage dump site justified eviction. Weissman believes that negative media coverage pressured then-mayor Mel Lastman to remove the growing community.

According to Cathy Crowe, co-founder of the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC), the silver lining in the death of Tent City was the launch of rent supplements for 105 of the former residents to obtain housing, a program which has been implemented in various provinces. The street nurse who once worked in Tent City deemed this solution a band-aid measure until the federal government funds a national affordable housing program.

According to Cathy Crowe, co-founder of the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC), the silver lining in the death of Tent City was the launch of rent supplements for 105 of the former residents to obtain housing, a program which has been implemented in various provinces. The street nurse who once worked in Tent City deemed this solution a band-aid measure until the federal government funds a national affordable housing program. Housepaint canvas houses will be auctioned online (bidding started on June 29) with all proceeds going to Habitat for Humanity Toronto (H4H), which constructs housing for families living in substandard conditions. Crowe believes that because H4H does not build for the homeless, there is still a frustrating disconnect, even though she thinks it is a wonderful organization.

Housepaint canvas houses will be auctioned online (bidding started on June 29) with all proceeds going to Habitat for Humanity Toronto (H4H), which constructs housing for families living in substandard conditions. Crowe believes that because H4H does not build for the homeless, there is still a frustrating disconnect, even though she thinks it is a wonderful organization. Ostrom believes that homelessness and affordable housing are part of the same continuum.

“The lack of affordable housing creates the conditions for homelessness. Housepaint, Phase 2: Shelter is about not only homelessness, but also shelter in general, hence the title,” said Ostrom, who has received a majority of positive feedback from members of the homeless community in Toronto who visited the exhibit.

“The lack of affordable housing creates the conditions for homelessness. Housepaint, Phase 2: Shelter is about not only homelessness, but also shelter in general, hence the title,” said Ostrom, who has received a majority of positive feedback from members of the homeless community in Toronto who visited the exhibit.

At the tunnel entrance of Housepaint, the words of Nancy Baker, the first resident of Tent City who is featured in Crowe’s book, Dying for a Home: Homeless Activists Speak Out, ran along both walls.“We all shared stuff down there, even food. It was home. Better than a park bench…Someday I’d like a balcony. After living at Tent City, I hate being closed in.”  *published in the July issue of the Ryerson Free Press

*published in the July issue of the Ryerson Free Press

*published in the July issue of the Ryerson Free Press

*published in the July issue of the Ryerson Free Press

No comments:

Post a Comment